Throughout history, markets have always re-created themselves, shifting the economic fortunes of those present at the creation. In this paper we discover how e-commerce alters the dimensions of time, place and form to alter fundamental notions of what a market is and how it operates. We explain what the shift from marketplaces to marketspaces means - and, what it portends. We look at new forms of intermediaries, cybermediaries. We explore the need for companies to appear in multiple, simultaneous roles in multiple, simultaneous marketspaces. Then we drill deeper to look at the business case for I-markets, their inter-enterprise business processes and the agile software needed to support new and changing business models. Armed with this framework, we move on to describe the key dimensions of strategy that companies will need in order to succeed as 21st century markets transform from places to spaces.

Contents

21st Century Markets

Business and Consumer Markets

Cybermediaries - Digital Brokers

Multiple, Simultaneous Market Models

The Business Case for I-Markets

I-Market Application Framework

Key Application Drivers of an I-Market

I-Market Business Strategies

Putting It All Together

"The marketplace is the place of exchange between buyer and seller. Once one rode a mule to get there; now one rides the Internet. An electronic marketplace can span two rooms in the same building or two continents. How individuals, firms and organizations will approach and define the electronic marketplace depends on people's ability to ask the right questions now and to take advantage of the opportunities that will arise over the next few years." - Derek Leebaert [ 1]."It's not hyperbole to say that the 'network' is quickly emerging as the largest, most dynamic, restless, sleepless marketplace of goods, services, and ideas the world has ever seen." - IBM CEO Lou Gerstner, speaking at CeBIT 98 in Hanover, Germany, predicted that the global e-Commerce will reach US $200 billion by 2000, an estimate that he considers conservative [ 2]."No company is an island, and industry boundaries are becoming blurred into new and evolving business ecosystems." - Component Strategies magazine, February, 1999 [ 3].As EDS' former CEO, Les Alberthal, explains, "By now we know the revolution will never abate. In the next 10 years we will witness one of history's greatest technological transformations, in which the world's geographic markets morph into one dynamic, complex organism" [ 4]. Such transformations do not occur with one big bang, nor are they a matter for tomorrow. Several industries have already been turned upside down and chaos hangs above other industries since, as Derek Leebaert writes, "Anyone with access to electricity can make a market at will."

21st Century Markets

Throughout history, markets have always re-created themselves, shifting the economic fortunes of those present at the creation. The dam on the Amstel river bears witness to the Dutch trading power that was driven by ships and trade winds as the medium of commerce [ 5]. In the 17th Century, the Netherlands was the leading maritime nation in the world. This "Golden Century," as it is known in Dutch history, was a period not only of great prosperity, but extended the wealth of its nation to art, architecture and culture that can be enjoyed to this day in the city built around the Amstel dam, Amsterdam.

Today's market re-creations are not paced by the speed of the winds moving merchant ships, they are happening at Internet speed. Rather than taking centuries to evolve, now the very notion of what a market is can change by the day - after all it is the "e-Commerce Century." How does a company build a "dam on the Internet" and create its Golden Century?

An Internet Market (I-Market) is the virtual place of exchange between buyer and seller in cyberspace. An I-Market is a virtual, digital marketspace where buyers and sellers congregate to buy and sell products and services. The "virtual" part eliminates the market-friction caused by the barriers of time (a customer can buy products 24 hours a day, 365 days a year), geographic location (from anywhere in the world), and form (for a growing list, atoms can be replaced by bits in delivering goods and services). No longer does a company need to have a physical presence to enter a new market. No longer are customers required to do business during normal business hours. Products often can make the leap from atoms (a compact disk, a software program, a bank statement, a check, or an airline ticket) to bits (MP3 audio, downloadable software programs, online financial statements and payments, or e-tickets). In one fell swoop, an I-Market can give a company an immediate, 24 hours x 365 days presence in the global marketspace. More importantly, it allows a company to more effectively meet the needs of its customers. Executed correctly, the results are new customers, increased loyalty from customers, increased sales and reduced costs. If executed poorly however, the results can be disastrous.

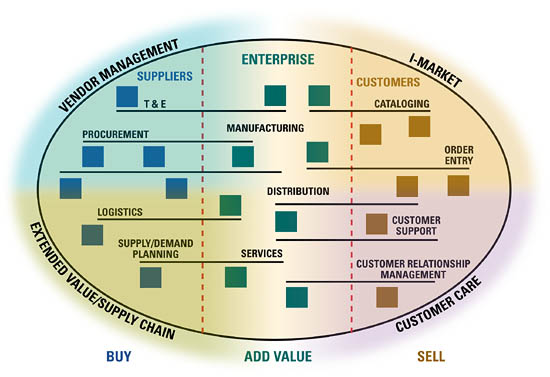

Figure 1 illustrates a small sampling of business processes being integrated electronically across corporate boundaries using e-Commerce as a business infrastructure. E-Commerce isn't a Web site, it's a completely new platform for a whole new way on doing business. To respond to the e-Commerce imperative, companies will need to change their business models, rethink the way they work and extend their internal business processes out to their suppliers, trading partners and customers.

As shown in the center of the figure, this new business infrastructure applies to all kinds of businesses: manufacturing, distribution or services. In any industry, an enterprise is located in a value-chain where it buys goods and services from suppliers, adds value, and sells to customers. Value-chain analysis was pioneered two decades ago by Harvard's competitive strategy authority, Michael Porter. Rather that outdate Porter's work, e-Commerce provides the business platform for realizing Porter's visions. On the sell-side of an enterprise, customer-facing processes include catalog management, order entry, customer support and overall customer relationship management. On the buy-side of an enterprise, supplier-facing processes include procurement and supply chain management, travel and entertainment, logistics and collaborative supply and demand planning.

Figure 1: Inter-enterprise Business Processes Enabled by E-Commerce Applications

As shown, an I-Market is one of four major categories of e-Commerce applications. On the buy-side are vendor management and extended supply chain systems. On the sell-side of any business, the customer-facing e-Commerce applications include I-Markets and Customer Care - these two, of course, are tightly integrated families of business processes and software applications. We separate the two in order to maintain focus and carry out an in-depth discussion of each. In our book, Enterprise E-Commerce, a full chapter is devoted to Customer Care, the other side of the I-Market coin. Here we focus on the business and technology issues, challenges and strategies of I-Market initiatives and applications.

Figure 2: A Top View of an I-Market

Figure 2 presents a top view of an I-Market - a new channel of communication and interaction between an enterprise and its customers. To be successful, an enterprise's I-Market initiatives must attract customers, handle customer transactions, and retain customers through excellent customer care. The entire framework must be carefully managed to bring about reliability, cost reductions and continuing process improvement - all judged from the customer's perspective. The benefits provided by e-Commerce must flow throughout the entire supply chain, from manufacturers, wholesalers and resellers to the ultimate customer. An I-Market serves communities of customers that, because they can collaborate, have the power to demand the best possible value. Anything less will not be tolerated - the Customer Age is about mass customization. It is about turning a company and its entire value-chain - over to the command and control of the customer - wow.

Business and Consumer Markets

There are two major types of I-Markets: business-to-business and business-to-consumer. With all the press hype over the business-to-consumer Net startups like Amazon.com, eBay and iVillage, the real business action of e-Commerce gets lost. In 1998, business-to-business e-Commerce was five times as large as the consumer sector. General Electric alone, for example, plans to purchase goods and services worth $5 billion over the internet in the year 2000. By 2003, Forrester Research calculates that the marketspace will grow to $1.3 trillion (that's $1,300,000,000,000.00) making up 9% of U.S. business trade - more than the GNP of the U.K. or Italy. From there, Forrester predicts that up to 40% of all U.S. business will be conducted electronically by 2006.

Although business-to-business and business-to-consumer models differ in many ways, they share core functionality. Whether a customer is a business or a consumer, I-Market applications need to manage customer profile information to customize the user experience and deliver personalized information (one-to-one marketing and service). Customers require easy-to-use capabilities to search catalogs and view products, to place orders, to review orders and to be notified when relevant events occur. These are some of the fundamental elements of a virtual I-Market that cross all market types and industry segments.

Cybermediaries - Digital Brokers

The digital broker is a cybermediary who adds value to and mediates between buyers and sellers. In the business-to-consumer marketspace, the broker functions primarily as an aggregator of disparate buyers and sellers. The broker aggregates supplier offerings, simplifying matching and searching for the buyer. Conversely, the broker brings an aggregation of potential buyers to the seller whose tasks of getting buyer attention is reduced. The broker model requires the functionality of both buy-side and sell-side forms of commerce plus sophisticated market processes for mediation between buyers and sellers.

The broker's role in business-to-business markets often requires a high degree of sophistication as dynamic trading networks go beyond content aggregation to process integration. Web sites built to support this domain are process-centric. They must align, integrate and automate business processes and rules. For example, a seller must cross company boundaries and integrate with the buyer's requisition approval processes in order to provide complete procurement solutions. In business-to-business markets the focus is usually on supply chain management where critical processes include forecasting, materials requirements planning, scheduling, manufacturing, logistics, and cost accounting. Information boundaries among participants must be carefully managed to preserve the unique business rules of each participant and provide one-to-one customization. Real-time event notification and workflow must cross disparate information systems and messaging protocols.

Within industries such as manufacturing or institutional brokerage, cybermediaries such as GE's Trading Process Network (TPN) will give rise to what Forrester Research calls "Internet commerce power grids," the backbone for dynamic trading processes. Currently, TPN provides the real-time connections among buyers, sellers and intermediaries through which catalog content, payments, bid/ask offers and digital goods flow. With systems such as TPN, flat supply chains become multidimensional matrices or power grids driving markets toward hyper-efficient means of production.

Multiple, Simultaneous Market Models

Portals, niche portals, vortexes, interoperating I-Markets and supply chain integrators are some of the terms that will soon be taught in graduate and undergraduate marketing courses. They are the new realities transforming classical channels of distribution. Because of the ubiquity of the Internet, a given company may need to support all these market models simultaneously.

Figure 3: A Multi-Market Scenario for Fruit of the Loom (tm)

Figure 3 shows a scenario most companies will need to embrace as I-Markets emerge and mature. The figure shows how a company like Fruit of the Loom may likely evolve its many I-Markets. Fruit of the Loom's Activewear division is a leading manufacturer of T-shirts, fleecewear and knit sport shirts in the imprinted sportswear market. The Activewear division offers a wide selection of apparel products for garment decoration, screen printing, embroidery, appliques, heat transfers and more. When FOL pioneered its Activewear Web site it became a "niche portal" for this particular industry segment. By providing hosting services for its small and medium enterprise (SME) Activewear distributors, it wisely locked in its position as an industry portal, even at the expense of allowing its distributors to carry competing brands (e.g. Hanes) at the site.

So, what is the best model for creating I-Markets? All of the above! Successful companies in the Information Age will deploy stand-alone corporate Web sites, establish brokerage sites, and participate in multiple marketspaces. Sub-forms of these marketspaces have already emerged. In a governed maketspace, interactions occur with the market, not the participants directly. In an open market or trading network, interactions occur directly between participants with the market only playing the role of mediation. In a closed marketspace, typical of supply chains, trading partners are tightly integrated and work from contracts, pre-negotiated pricing and rules of engagement.

Again, what is the best model for creating I-Markets? In actuality, the best model is an agile model. Agility is the key to riding the waves of e-Commerce. Amazon.com began as a simple I-Market, an online bookstore. As CEO, Jeff Bezos, remarked, "We had a world class site the day we launched - but it is only a tenth as good as the site we have now" [ 6]. He went on to say that they have only 2% of what they will need in the coming years. Not only has the site itself grown in robustness, it has positioned itself at portals such as ABCNEWS, Netscape and eXcite. With its zShops, PlanetAll, and auction services, it aspires to be a vortex, a Web-based market-maker that brings together a fragmented group of buyers with an equally fragmented group of sellers.

Positioning and rapid evolution are essential to success in I-Markets. It is not enough to establish a transaction enabled Web site. The I-Market pioneers have been nimble, innovative, experimental and brave. They have learned that their business models will change in concert with rapidly changing marketspaces and opportunities. The secret is to build a business metamodel that is agile enough to support new and changing I-Market models as the infant world of digital markets matures to become the digital economy. In the 17th century, Amsterdam became the vortex of the new merchant class. Societies were transformed. The building of the 'Interdam' will be a feat of historical proportions.

The Business Case for I-Markets

I-Markets make for interesting investment propositions in that they provide double leverage. They can increase revenues and decrease costs, simultaneously. This fact alone deserves a "wow," for not many business resources can do that.

A well-designed I-Market can deliver multiple revenue opportunities:

- As a new, global distribution channel, an I-Market allows a company to reach new customers.

- An I-Market can provide better customer access to a company's products and services. In the form of one-to-one marketing, each customer can have personalized access.

- Convenient access can enable a company to obtain significantly more information about customers and their buying behavior. This information represents a new way to learn which customers actually contribute to the bottom line. By allowing a company to concentrate on the needs of its best customers, new profit opportunities become visible.

- Up-selling and cross-selling opportunities can empower a company to expand its product lines and offer more goods and services to the customer. In complex purchases such as buying real estate, the many ancillary processes (insurance, moving and storage, financing and so on) can be aggregated to provide the customer with "total solutions." A company can expand its product and service lines to offer complete solutions, changing the very nature of the business: what and to whom it sells.

- By focusing on customer behavior, one customer at a time, ever-changing needs can be met through offering new, personalized products and services. One-to-one marketing is the new frontier for competitive advantage.

- With ongoing, instant access to supply and demand information, an I-Market provides marketers new opportunities for managing pricing policy as a marketing strategy in real-time. As I-Markets continue to grow, fixed pricing will be an artifact of history. "Fixed pricing" is a recent phenomenon and the case for "dynamic pricing" is compelling to both buyers and sellers.

- In concert with the previous point, companies can use their I-Markets to conduct auctions. This capability offers a new channel for moving surplus goods and one day may lead to most markets operating much like a stock market. Further, as automated buying software becomes applied to auctions, they will no longer be auctions. They will morph into dynamic pricing mechanisms needed to support almost "perfect competition" and market equilibrium. That is, of course, a long-range possibility. In the meantime, auctions are already a powerful means to draw both consumer and business traffic.

- An I-Market, in conjunction with complete customer care offerings, can build customer loyalty through personalized service. For example, in the business-to-business market, a seller can build customer loyalty by tying into and supporting the buyer's internal business processes such as requisitioning and purchasing approvals. Loyal customers sell themselves and can be counted as part of a company's sales force as they spread the word.

New and radical cost saving opportunities are many:

- An I-Market can significantly reduce the costs associated with processing sales transactions, fully automating the transaction life cycle.

- An I-Market can significantly reduce marketing costs. While the cost of developing quality marketing materials does not change, their distribution is essentially free via the Web. Electronic brochures, catalogs, and other forms of company and product information can be disseminated without incremental cost. A brochure can be read by millions as readily as by one - no printing, mailing or distribution required.

- I-Markets with real-time connection to their supply chains, can significantly reduce or even eliminate warehousing, shipping and inventory costs.

- An I-Market can significantly reduce customer care costs, while increasing quality and fostering loyalty.

- When bits can replace physical media, an I-Market can eliminate the manufacturing costs of burning information onto paper and plastic and moving it from the manufacturer through the supply chain to the customer. In an I-Market, just the information moves and its medium is essentially free. Software, music (MP3), research services, electronic tickets (eTickets) and magazines (eZines) are but a few of the growing lists of products and services being delivered through digital channels of distribution.

- When complex products or services are being sold, costs can be significantly reduced by supplying customers with digital planning, specification and configuration facilities. Such "self-selling" can reduce errors, costs of shipping and returns processing, and costs associated with maintaining a staff of sales engineers and other highly trained knowledge workers.

Several I-Market pioneers have already changed their business models and offer lessons learned along the way. Their stories are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Industry Examples of I-Markets

A premiere example of an open business-to-business I-Market is TPN Register. TPN Register, LLC is a 50/50 joint venture between GE Information Services, a global leader in electronic commerce services, and Thomas Publishing Company, publishers of the Thomas Register of American Manufacturers. These parent organizations have been using both technology and information to facilitate sourcing and enhance inter-enterprise relationships between buyers and sellers for decades. TPN Register applies this expertise to provide comprehensive Internet commerce solutions for industrial buyers to procure MRO (Maintenance, Repair and Operation) and other indirect goods and services. TPN Register provides services that enable corporations and their trading partners to streamline the procurement of MRO supplies and services. TPN Register creates, customizes and hosts secure, private electronic catalogs that contain accurate, searchable and comprehensive product data that integrates with legacy and ERP environments. TPN Register works with both buyers and sellers to build electronic trading communities that benefit all participants.

As previously mentioned, Amazon.com is probably the most widely referenced example of a business-to-consumer I-Market. Beginning with books and tools to establish a collaborative community-of-interest, the eTailer is an outstanding example of a new market entrant that was first-to-market in the digital world. Being first-to-market with a high quality site resulted in an eBranding coup d'état. While selling books and establishing its brand, Amazon.com keeps running hard. They have expanded their product line to include audio, video, gifts, toys, electronics and drugs. If Amazon's newly launched zShops gain acceptance by merchants who, frankly, are afraid of being reduced to commodity vendors, Amazon.com will likely become "Earth's largest everything store," offering just about anything a consumer could want to buy. Backing this ambition, Amazon.com's growing customer database positions the company with the greatest business asset in the 21st century: broad and deep information about customers and their buying behavior. To add even more substance to its customer database, Amazon.com's PlanetAll offers free, self- updating address books, calendars, and ad-hoc discussion groups for personal information management. The company is an exemplar of a totally customer-driven enterprise.

In making the Business On The Internet (BOTI) Awards, [ 7] Brian Walsh commented, "It's not much fun to nominate a large, well-known company as the best business-to-business electronic-commerce site. It would have made better copy to nominate a small bootstrap operation - one that pursued the Internet dream on a shoestring, using it as a way to steal marketshare from a large competitor. However, it's hard to argue with success - Cisco's site is an example of a complete, effective approach to the challenges of delivering E-commerce solutions to the widest possible audience." As of December 1998, Cisco conducted almost 70% of its commerce transactions via the Web, and anticipates over $6 billion of its $10 billion run rate for Fiscal Year 1999 [8].

In the financial sector, Wells Fargo first offered online banking in 1989 and Internet services in May 1995. Wells Fargo customers can bank online through the Internet using Quicken and Microsoft Money. Consumers can pay bills to anyone in the U.S. using each of these channels. They may also view their account information and transfer money between their checking, savings, credit card, line of credit and money market mutual fund accounts. Customers using the Internet can apply for new accounts and download account history into personal financial management software. Customers who apply online for home equity credit receive instant decisions, without waiting several days for a response. Other services, such as check reorder, address changes and travelers checks are also available over the Internet.

I-Market Application Framework

Having defined what they are and why they are so important to the bottom line of a business, we can gain a deeper understanding of I-Markets by examining the business processes that an I-Market must support and the application drivers needed to implement these processes in software.

I-Market Business Processes

Although each type of I-Market has it's own set of activities, many are common to all market types and can be represented by looking at the life cycle of a selling/buying transaction. Table 1 shows several marketplace life cycle models differing in levels of complexity and the number of steps involved: buying a book is a short and simple process (see-buy-get), while contracting for components to build a commercial airliner is a long-lived, complex proposition.

Table 1: Various Marketplace Life Cycles See - Buy - Get Information stage (electronic marketing, networking), Negotiation stage (electronic markets), Fulfillment stage (order process, electronic payment) and Satisfaction stage (after sales support). Discovery, Evaluation, Negotiation, Order Placement, Scheduling & Fulfillment, Payment, Receiving, Billing, Customer Service/Support The functions and capabilities underlying most transaction life cycles in an I-Market are listed in Table 2. Although the overall life cycles are roughly the same, business-to-business I-Markets must have an emphasis on custom catalogs that reflect pre-negotiated pricing, different forms of payment (credit cards are seldom used in business-to-business transactions), integration with existing EDI systems, and workflow engines that are generally needed by both buyers and sellers in business-to-business trade.

Table 2: Typical Components in I-Markets Business-to-Consumer Business-to-Business Content publishing tools

StorefrontsAuctions

Access management, authentication Merchandising: promotions, coupons

E-mail, Chat

Catalogs

Classification search

Product Configurators

Profiling and personalization

AggregationOrder Processing

Credit Authorization

Payment Facilities

Fulfillment

Business Rules Facility

Order Tracking

Customer Service

Reporting

Integration to Back Office: product data management and ERP systemsContent publishing tools

Access management, authentication

Bid/ask trading

Auctions, on-sale

Catalogs, Custom catalogs

Parametric Search

Product Configurators

Aggregation

Supplier ManagementOrder Processing

Invoicing

EDI integration

Event notification

Fulfillment

Business Rules facility

Payment facility

Workflow

Reporting

Integration to Back OfficeA simplified lifecycle (Marketing, Catalog Management, Order Processing, Fulfillment, and Settlement) is sufficient to describe the key inter-enterprise business processes common to all forms of I-Markets. These core business processes appear at the center of Figure 5.

Figure 5: I-Market Application Framework

Going further, Figure 6 peels back another layer of the I-Market model to reveal some of the activities and tasks of the key business processes. To explore these processes, each is first discussed in context of business-to-consumer I-Markets, followed by a discussion from the perspective of business-to-business I-Markets.

Marketing

Customization is the by-word of the 21st century marketing revolution. By interacting with customers electronically, their buying behavior can be evaluated and responses to their needs can be tailored. Customization provides value to customers by allowing them to find solutions that better fit their needs and saves them time in searching for their solutions. Instead of presenting a huge catalog to a given customer to sift through, custom catalogs can be presented, one customer at a time. Not only can a solution be pinpointed for a customer, but also as the relationship grows, the more a business knows about individual buying behavior. As a natural result of the growing relationship, cross-selling opportunities will abound. With the Net, the savvy marketer can sense and respond to customer needs in real-time, one-to-one. In addition to demographics, the electronic marketer can track biographics: the life passages and temporal events that shift the interests of the individual. For instance, buying one's first home is a life passage event that can lead the marketer to target the consumer for a range of products and services from life insurance to home furnishings.

In the world of electronic consumer markets the success factor mantra is: relationship, relationship, and relationship. Successful marketers have shifted their focus from products to the customer - the whole customer. The goal is to build an ever-deepening relationship with a customer to meet as wide a variety of the customer's needs as possible.

The business that owns the primary customer relationship is the business that excels at electronic commerce - they will be the first place a consumer will go to meet their shopping needs. Considering that it is five to eight times more expensive to gain a new customer than it is to sell to an existing customer, the stakes are high indeed. Companies that are able to capture substantial information about their customers' buying behavior can anticipate needs for goods and services of all kinds - this is the essence of one-to-one marketing where each customer is treated as a market segment of one.

Figure 6: I-Market Business Processes

The Internet provides two-way information opportunities and benefits not available through traditional retail channels. Initial success in the business-to-consumer marketspace can produce new sources of revenues and cuts costs of marketing and delivery of goods and services.

What is involved in a robust business-to-consumer system that draws customers and promotes return visits? A well-designed consumer oriented system will mimic the way people shop. When Intuit introduced its home bookkeeping system for the personal computer, Quicken, it was a smashing success. People already knew how to write a check. Intuit capitalized on what people already knew and gave them direct manipulation of a checkbook as the user interface to their system. The computer per se disappeared from the mind's eye of the user; they were simply using their checkbook digitally - no training required. In addition to the intuitiveness, the software added value by taking care of the tedious work of calculating balances, reconciling to the bank statement and maintaining the budget.

People already know how to shop. A well-designed business-to-consumer application will capitalize on what they already know. Understanding and modeling the consumption process is key to designing a system that is not only simple to use, but can add significant value for the shopper. It is not enough to take a company's catalog and place it on a Web site with an order form. Consumer-oriented systems need to be designed from the customer's perspective, from the outside, in.

Getting noticed and attracting customers is just as important in consumer-oriented e-Commerce as it is in the physical world of retailing. Thus, advertising on the Web is essential as the retailer still must compete for the attention of potential customers. Web advertising takes on many forms including placing banner ads on popular sites ( CNN, local or regional newspapers, industry niche portals, trade associations, or general Internet portals like Excite or Netscape). Another major shotgun form of advertising is registering Web sites with the major search engines (e.g. Hotbot, Yahoo, and AltaVista). According to the eAdvertising Report by eMarketer, American companies spent $1.5 billion on Internet advertising in 1998. The research firm estimates that the figure will increase by 73 percent to $2.6 billion by the end of 1999, and to $8.9 billion by 2002 [ 9]. In the international markets where Web advertising is less developed, including Europe, Asia, and Latin America, less money is spent on Web advertising. eMarketer found that only $132 million was spent on Web advertising in Europe in 1998.

Advertising must go beyond the Internet itself. The "www.company.com" hallmark is already standard fare for magazine ads, billboards and broadcast media. "In the mad race to build awareness, establish online brands and drive site traffic, Web marketers will continue to divert the majority of their advertising and marketing budgets to offline media and their own corporate Web site development," said eMarketer's Geoffrey Ramsey. "The brand battle for Web marketers will be waged, not so much on banner ads, but on television sets, radios, and in magazines, as well as on company Web sites where real consumer interaction takes place."

Merchandising is a marketing tool of long standing and applies to business-to-consumer e-Commerce as well. Consumer-oriented systems need to include the digital counterparts for coupons, promotions and sales. Shoppers like to browse and bargain shop. A retail Web site must have an attractive storefront that entices the browser inside. Giving away useful information or digital coupons for entering are two such techniques.

Catalog Management

Once inside an I-Market, the potential customer must be free to browse. The catalog of goods and services must be extremely easy to navigate, letting the shopper browse just the aisles of greatest interest without having to go through an entire catalog. The buying process, however, may not be as straightforward as a simple catalog search. The customer's buying process may involve many steps and decision points (for example, vacation planning) and require information from multiple sources. When there are many sources in the search space, the buyer can be overwhelmed by search engines. In this case the seller may take on the role of broker or aggregator in order to add value by bringing together the needed resources.

When entering a consumer-oriented site, the user may be offered the option to register with the site to better serve him or her, but this should not be a prerequisite. Access control is important to all forms of e-Commerce, but in the consumer space, browsing a catalog should be open to anyone. Even if users do not register interests and preferences, the click streams they create while browsing can be used to personalize the experience. High-end or specialty goods and services require much more information than commodities. For such items, chat rooms, collaborative filtering, e-mail, electronic newsletters and similar technologies can add great value to the consumer experience. These technologies allow the seller to build communities-of-interest at their site. Should the browsing consumer or community participant decide to buy, then the purchase becomes the trigger point for obtaining initial customer information.

Order Processing

The move from providing electronic information and building electronic relationships with the shopper to conducting the electronic transaction must be seamless. While browsing, but not yet taking the decision to buy, the site will likely provide a shopping cart where the consumer can place tentative selections. Once browsing is complete, the shopper should be able to review the cart and discard those items he or she decides against as they proceed to the "check-out" lane.

As the shopping process enters the electronic transaction stage, the first step with a new customer is gathering essential customer information: name, primary address, billing address, shipping address, and payment method for the transaction. The first step with an existing customer is authentication. Once the identity is verified, much of the information in the customer's files can be reused to complete the current transaction. Completing an order requires payment authorization, usually from links to credit card services on the network where the payment funds are committed. Additionally, taxes and shipping costs must be calculated. Finally customer confirmation of the order with details of any back ordered items must be produced as a customer receipt, and typically e-mailed to the customer.

Fulfillment

Completed orders progress to a fulfillment stage that may be as simple as preparing picking and packing slips for the warehouse, or initiating the process of aggregating the items from many sources, or as complex as triggering workflows in a supply chain for made-to-order goods. In addition, fulfillment may be completely digital when the product or service being sold is information. Digital fulfillment means granting access to the information, such as a subscription to the New York Times, or downloading software from Egghead.com. With fulfillment completed, the transaction moves on to settlement where funds actually transfer to the seller. Throughout the process, customer service facilities are needed to allow the customer to inquire about the status of the order and handle exceptions.

Settlement

Credit cards play a central role in business-to-consumer I-Markets. SET (Secure Electronic Transactions) is a system for ensuring the security of financial transactions on the Internet. With SET, a transaction is conducted and verified using a combination of digital certificates and digital signatures among the purchaser, a merchant, and the purchaser's bank in a way that ensures privacy and confidentiality. In business-to-business I-Markets, procurement cards (P-cards) from companies like MasterCard provide functionality comparable to consumer credit cards. With recent P-card initiatives, line item detail can be tracked for reconciliation back to general ledger accounting records. Further, high volume transactions in trading networks are settled with existing EDI facilities. Standards for payment gateways are being developed and will ultimately simplify the connections made from any given I-Market to all forms of secure electronic payments.

The inter-enterprise processes described for I-Markets are, of course, more elaborate than highlighted in the paragraphs above. These summaries, however, do provide a high-level view of the major activities common to I-Markets. Reflecting on these five business process areas and their multiple options, it can be readily seen that no pre-packaged point solution can possibly hope to meet the unique needs of all companies and provide the agility companies need to compete in dynamic markets.

Business markets

The key shift in focus from addressing the business-to-consumer market to the business-to-business market is one from shopping to procurement. Currently, the business-to-business market is about 100 times greater in transaction volume than the business-to-consumer marketspace. Much of the future growth is expected to involve small and medium sized firms that were not able to participate in e-Commerce prior to the availability of the low cost, highly accessible Internet.

Procurement differs from shopping in several ways. Purchasing departments are under pressure to get orders placed quickly and efficiently. Almost by definition, the professional buyer or purchasing agent is a repeat customer. In order to complete their work within time constraints, reuse of data and authorized access information must be available from buying session to buying session. Purchasing agents do not engage in impulse buying. Often they buy from suppliers where the terms and condition of trade are pre-negotiated. While merchandising, coupons, and up-selling are essential in the business-to-consumer market, they are largely irrelevant to the business-to-business market.

In the online business-to-business marketplace, the seller's first concern when a potential purchaser connects to do business is authentication so that custom pricing and custom catalogs can be presented to the purchasing agent. Not all transactions, however, are based on simple catalog selections. Configuration processes may have to be designed and implemented, or the seller may be participating in bid-ask procurement scenarios. In addition, features must be available in the seller's systems to be able to conduct auctions and promote items put on sale to move discontinued inventory. On the buyer side of transactions, a purchase request may need to be routed to a designated purchasing agent who in turn must obtain approval before committing to placing an order.

One of the most widely used business-to-business applications of e-Commerce addresses Maintenance Repair and Operations (MRO) procurement where businesses buy non-production goods and services from custom catalogs: office supplies, repair parts, cleaning supplies and facility maintenance items and services. As much as 30% of the total cost of doing business falls into this category. That fact alone makes it obvious why companies have rushed to use the Internet to reduce costs. These are high volume, low value purchases that are repeated routinely. They involve high order processing costs for the buyer and supplier, relative to the item costs of each order. Before the advent of e-Commerce, it could take $10 in purchasing costs to order a $1 box of paper clips.

Although MRO is the initial killer application of business-to- business I-Markets, integrating business processes between and among players in value chains will earmark future development. In short, business-to-business e-Commerce is about dynamic process integration. Inter-enterprise Process Engineering (IPE) provides the foundation for competitive advantage. Process integration is possible at three levels: intra-company via intranets; between tightly aligned partners via extranets; and in an ecosystem of trading processes established dynamically, possibly in real-time, via the Internet. Open business I-Markets such as TPN Register are pursuing this progression to the future. As a prime example of a double-edged sword, the amount of complexity and the potential for competitive advantage increase at each level of process integration.

Key Application Drivers of an I-Market

A core set of application drivers is needed to implement I-market business processes in software. These include Information Boundaries, Workflow/Process Management, Data/Process Integration, Searching and Information Filtering, Event Notification, and Trading Services facilities, as shown in Figure 7.

Information Boundaries

Profile management application facilities are needed to manage information boundaries between the selling company, its customers, suppliers and third party entities such as shipping and payment services. User authentication, authorization and access controls are maintained by profile management software and facilities.

Dynamic profiling is essential to customization, the key to one-to-one marketing. Customer privacy, however, is critical throughout the profiling process. The Open Profiling Standard (OPS) is a proposed standard for how World Wide Web users can control the personal information they share with Web sites and I-Markets. Standards that protect the privacy of the customer are absolutely necessary for the widespread acceptance of e-Commerce. Companies must design their information boundaries to comply with appropriate profiling standards.

Figure 7: Key Application Drivers for I-Markets

Workflow/Process Management

Workflow facilities are needed for processing credit authorizations and driving ordering, fulfillment, shipping and settlement processes. Workflows between the seller and its suppliers must be tightly integrated so that customers can be fully informed throughout the ordering and fulfillment processes. In business-to-business I-Markets, workflow is also essential to the approval processes within the buying organization as well as the selling company and its trading partners. In governed markets, workflow facilities are a major part of what the market makers provide. In open markets, workflow facilities of the individual participants play a principle role.

Data/Process Integration

Data integration is essential to catalog aggregation and management, pricing, and inventory management - in real-time, across the supply chain. I-Markets must be integrated with existing resource management and accounting systems of the selling enterprise - the same holds true for buying organizations in business-to-business markets. Of special importance is integration with a product data management system so that catalogs in all media (paper, CD-ROM and online) are synchronized. When build-to-order marketing is employed, product data integration must extend into the realms of engineering and shop-floor production support systems.

Event Notification

Event notification facilities are essential for providing sellers, customers and suppliers with notifications of exceptions, changes and other situations requiring their attention. As the Web reaches out to more and more devices (pagers, PDAs, telephones, and faxes) to support a growing mobile workforce, event notification facilities must accommodate each of these customer touch points. Event notification facilities are also essential for application-to-application interoperation. For example, when a back ordered item is received, the receiving event triggers the shipping and payment processes of fulfillment and settlement. Applications subscribe to and are notified of events that affect them - such messaging is at the heart of robust I-Markets which, by their very nature, are event-driven systems.

Trading Services

Robust I-Markets include dynamic trading services facilities. Going beyond simple catalog sales, trading services are needed to provide discovery, mediation, matchmaking, negotiation and collaboration environments. Trading services facilities underlie auctions and are the foundation for building communities-of-interest. Trading services facilities will become very sophisticated as I-Markets become more advanced in response to growing demands from customers.

Searching and Information Filtering

Searching and information filtering facilities are needed by all I-Market participants. Business-to-consumer search requirements may be simple and basic key word or hierarchical search may suffice to allow users to browse through various categories in a catalog.

At the heart of one-to-one personalization and community building is a technology known as "collaborative filtering." The technology can be used to collect ratings about items available in an I-Market. By making the sales rankings available as a customer browses an item, customers can see similar items with high rankings by other customers. For example, a customer browsing a particular book title can see what other customers bought who also bought the book being browsed. Once an I-Market has collected a critical mass of ratings, it can respond to customer inquiries with recommendations that are tuned to customers' preference patterns. Customer-driven collaborations and buying patterns tracked by collaborative filtering facilities also can be used to achieve advertising precision never before possible - the ultimate tool for up-selling and cross-selling.

I-Market Business Strategies

In their often-documented success, Cisco Systems' executives reflect on lessons they learned and offer their prescription for success. "1. If you're not adding value for the customer, don't bother. 2. Know who your target audience is. 3. Listen to your customers. 4. Start small. 5. Focus on quick payoffs first. 6. Combine traditional marketing and new media to promote the site. 7. Expect Success: plan to expand infrastructure quickly. 8. Market the applications both internally and externally" [ 10].

The starting point for any successful I-Market initiative is a deep understanding of a company's customers. What are their e-Commerce expectations? What is their Internet readiness? How can the I-Market add value? Whether in business-to-consumer or business-to-business environments, the "consumption process" must be engineered to provide total solutions to customers. Channel conflict is a part of the equation of providing total solutions to customers. Should an enterprise dis-inter mediate or support its existing distribution channels? Answers to these questions are determined by how the customer perceives the value-add of each entity in the overall value/supply chain. For example, if the customer sees no value in keeping travel agents in the supply chain when their role would be reduced to distributing the physical ticket, dis-inter mediation makes sense. When customer service and support are key ingredients, the value-add is usually such that distributors and other intermediaries in the value/supply chain are critical, and reinforcement of existing channel partners makes sense. In short, evaluation of the customer-centered value/supply chain comes first in determining the appropriate business model. I-Market strategy is about new business models - simply setting up a Web site to display a company's existing products and take orders is the least likely road to success.

For all but simple catalog commodities where the sales transaction is "see-buy-get," customers want help. They want their buying experience to be intuitive and the information they access to be robust. Lands End's "Your Personal Model" offers an interactive shopping experience where the customer supplies information about their hair color, height, shoulders, hips, waist, waist placement ... and a name for the personal model. Then clothes are checked out to a dressing room where they can be tried on the model. Adding visual and sensory aspects to the buying process, Garden.com lets customers download its interactive garden planner software where plants can be selected and dropped onto a planning grid or an existing garden template can be used to jump start the design. Once design is complete, a click of the mouse adds the plants to the shopping "wheel barrow" and proceeds to the check out lane. In business-to-business consumption processes, equally intuitive and useful tools are needed, and the process must cater to internal approval cycles of the buying company.

A common mistake an enterprise can make is to view the development of an I-Market as a singular event, resulting in a single Web site I-Market. This perception is short-sighted and has strategic consequences in the emerging worlds of open markets and digital business ecosystems. A given enterprise will participate in multiple I-Markets simultaneously. For example, Hilton Hotel "Web site" replicates itself and lives inside I-Markets formed by travel agents, tourism promoters and airlines. Corporate strategists need to think in the plural form, "I-Markets," and adopt an approach that can sustain the building of multiple, simultaneous business initiatives. To be practical, the approach must rely on a core set of reusable software components.

Putting It All Together

Enterprise-class I-Markets harness the Internet to automate the business processes of selling a company's products and services. An I-Market can deliver a double impact, reducing costs while increasing revenues. A sustainable approach to implementing multiple I-Markets levers legacy enterprise systems and extends them to customers and the enterprise's trading partners. Howard Anderson, Founder of The Yankee Group and Battery Ventures confirms, "Every company has built order entry systems, customer support systems, and sales automation systems. What the smartest are doing is turning that embedded cost into "customer-facing" systems. By putting a user-friendly front end on top of a tried and true internal solution a company can build a strategic advantage. A company has achieved double leverage." Of course the tasks at hand are more than just putting a pretty face on top of existing enterprise management systems. Putting it all together for next generation I-Markets means extending core business processes with e-Commerce application drivers as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Putting It All Together

Companies that already have mastered I-Markets have turned complete industries upside down. Competing against them will be increasingly difficult. And these pioneers show no sign of slowing their pace of new developments. They have recognized Kevin Kelly's New Rules for the New Economy. Kelly fully describes the shift from places to spaces, "Place still matters, and will for a long time to come. However, the new economy operates in a 'space' rather than a place, and over time more and more economic transactions will migrate to this new space. People will inhabit places, but increasingly the economy inhabits a space. Your worst nightmare of a competitor is now only one-eighth of a second away" [ 11].

Companies that may think that e-Commerce is a fad, or at most the act of establishing a Web site, should read what one 90-year old senior citizen has to say, "The truly revolutionary impact of the Information Revolution is just beginning to be felt. But it is not "information" that fuels this impact. It is not "artificial intelligence." It is not the effect of computers and data processing on decision-making, policymaking, or strategy. It is something that practically no one foresaw or, indeed, even talked about ten or fifteen years ago: e-commerce -- that is, the explosive emergence of the Internet as a major, perhaps eventually the major, worldwide distribution channel for goods, for services, and, surprisingly, for managerial and professional jobs. This is profoundly changing economies, markets, and industry structures; products and services and their flow; consumer segmentation, consumer values, and consumer behavior; jobs and labor markets. But the impact may be even greater on societies and politics and, above all, on the way we see the world and ourselves in it."

The father of modern management, Peter Drucker, goes on to compare the steam engine to the computer. "The steam engine was to the first Industrial Revolution what the computer has been to the Information Revolution - its trigger, but above all its symbol." In 1776 the steam engine made it possible to mechanize the manufacturing process. By itself, the steam engine did not create the Industrial Revolution - it was necessary, but not sufficient. It was decades later that something totally unexpected happened - "Then, in 1829, came the railroad, a product without precedent, and it forever changes the economy, society and politics." With their ability to distribute mass produced goods, "the western world was engulfed by the biggest boom history had ever seen - the railroad boom. The railroad was the truly revolutionary element of the Industrial Revolution."

By itself, the computer has not created the Information Revolution. Since its introduction in the 1940s, the computer has only transformed processes that were here all along. Now, decades after the advent of the computer, Drucker describes the true meaning of e-Commerce, "E-Commerce is to the Information Revolution what the railroad was to the Industrial Revolution - a totally new, totally unprecedented, totally unexpected development. And like the railroad 170 years ago, e-commerce is creating a new and distinct boom, rapidly changing the economy, society, and politics" [ 12].

To win in 21st century markets, a company should start by identifying its unique requirements and issues - independent of the packages available on the market - then select low hanging fruit for initial implementation projects. Central to this approach is the reuse of a common core of e-Commerce application components to incrementally develop new applications and grow their capabilities as new market opportunities are discovered. By adopting a component-based development approach for agile software development, companies can implement breakthrough I-Markets today and take advantage of new opportunities that will appear tomorrow.

About the Authors

Peter Fingar is Technology Advocate for EC Cubed.

E-mail: pfingar@tampabay.rr.comHarsha Kumar is co-founder of EC Cubed and serves as the Director, Product Strategy.E-mail: hkumar@eccubed.com

Tarun Sharma is co-founder of EC Cubed and serves as Director, Product Management. E-mail: tsharma@eccubed.com

Note

This paper is based in part on portions of Peter Fingar, Harsha Kumar & Tarun Sharma's book Enterprise E-Commerce: The Software Component Breakthrough for Business-to-Business Commerce published by Meghan-Kiffer Press, Tampa, Fla. (ISBN 0-929-65211-8). Available from amazon.com and elsewhere.

References

1. Derek Leebaert (editor), 1998. The Future of the Electronic Marketplace. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

2. "IBM's Gerstner Speaks On E-Commerce," Newsbytes News Network, 19 March 1998.

3. Peter Fingar, 1999. "Blueprint for Open eCommerce," Component Strategies (February).

4. Les Alberthal, 1998. "The Once and Future Craftsman Culture," In: Derek Leebaert (editor), The Future of the Electronic Marketplace. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

5. "The Marketspace: eCommerce in the Digital Economy," Tampa Regional Technology Council meeting, 19 April 1998.

6. "Jeff Bezos: selling books, running hard!" Forbes ASAP, 6 April 1998.

7. "Best site for business-to-business commerce," http://www.internetwk.com/BOTI/boti2.htm

8. http://www.cisco.com/warp/public/146/november99/15.html

9. http://www.cyberatlas.com/segments/advertising/emark.html

10. Kate Maddox, 1998. Web Commerce. New York: Wiley, p. 42.

11. Kevin Kelly, 1998. New Rules for the New Economy: 10 Radical Strategies for a Connected World. New York: Viking Press.

12. Peter Drucker, 1999. "Beyond the Information Revolution," Atlantic Monthly (October).

Editorial history

Paper received 13 November 1999; accepted for publication 22 November 1999; revision received 24 November 1999; revision received 6 December 1999

Copyright © 1999, First Monday

21st Century Markets: From Places to Spaces by Peter Fingar, Harsha Kumar and Tarun Sharma

First Monday, volume 4, number 12 (December 1999),

URL: http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue4_12/fingar/index.html