The paper presents the characteristics and trends of the Internet and e-commerce in Japan. Then it discusses the results of a content analysis of the top 50 popular Web sites in U.S. and those in Japan conducted in November 1999 and May 2000. This study examines cultural differences in the use of the Web in each country and suggests strategies for global e-commerce.

Contents

Importance of Going Global

Internet Users in Japan

Content Analysis of Popular Web sites in Japan and the U.S.

Conclusions

Importance of Going Global

With the ability of the Web to instantaneously reach a global audience, many e-commerce and e-business companies have attempted, or are attempting, to expand their markets beyond their home countries. As the number of Internet users grows at an exponential rate around the globe, there are great opportunities for companies to grab a share of the global market through the Web. Currently about 49% of the Internet population is estimated to be non-English speakers; by 2003 75% of the total Internet population is expected to be non-English speakers [ 1]. In 1999 the U.S. accounted for 62% of all e-commerce spending in the world. In 2003, about 56% of e-commerce transactions are expected to be conducted outside the United States [ 2]. Shortly after the turn of the new millennium, English-speaking audiences may no longer dominate the Internet.

Expanding business through the Web may not require physically setting up offices physically in different regions or countries. If a business has already developed a Web site, it is important to translate the site into the target language of a particular foreign market. It sounds easy, but is a literal translation all that's required for a different culture?

According to Adam Jones, director of customer programs at SimulTrans, a translation company based in Silicon Valley, there are five basic localization strategies:

- Use only U.S. English;

- Translate portions of a given Web site into a target language;

- Translate the entire Web site into a target language;

- Culturally localize the site for a target audience; and,

- Develop content in a target country, independent of the U.S. site [3].

The first three strategies involve linguistic translation of Web sites whereas the last two strategies involve cultural translation. Cultural translation goes beyond mere linguistic translation since it involves designing a Web site that is sensitive to the cultural differences between the originated country and the target country.

Localization of an e-commerce site also goes beyond the localization of a mere Web site. It involves more than just files residing on a server; it involves the entire infrastructure necessary for transaction, distribution, and customer services, which is often unique to a specific country and tied to a specific culture. Each country in the world has a distinct social system and culture. Nothing cannot be generalized in discussing specific localization strategies for a particular country. Hence, in this paper, the Internet and e-commerce strategies in Japan are examined as a case study of unique cultural e-commerce strategies.

Internet Users in Japan

According to the top-level domain survey by the Internet Software Consortium in January 2000, Japan has the second highest number of hosts in the world (about 3.6% of the total number of hosts worldwide) following the U.S. (with 73.4% of the total number of hosts). In terms of the Internet population, Japan had 27 million users by the end of 1999, including those users who access the Internet through wireless phones, video game devices, and Internet appliances (a 59.7% increase from the previous year). The U.S. has 106 million users [ 4]. However, Japan ranks only ninth in terms of the number of hosts per capita.

The number of women using the Internet is rapidly increasing in Japan. According to the 2000 Tsushin Hakusho by MPT [ 4], 42% of the Internet users in Japan are women. Internet users in Japan tend to be younger than those in the U.S. In Japan, 76% of the users are in their 20s and 30s while in the U.S. those with ages from 18 to 54 comprise 60% of the total users. Among those people in Japan who access the Internet at least once a day, 92% of them use the Internet to check e-mail; 84% of them use it to surf the Web [4].

Most Internet users in Japan are very conscious of the time spent online as the dominant telephone carrier, NTT, still charges per minute telephone fees. This is not mitigated even by the fact that over 20% of Japanese homes use ISDN lines [ 5] as ISDN lines are also charged per minute of use.

Approximately 85 percent go online at least once a day and 64.6% of those Japanese Internet users have had some experience of buying online [ 6]. In the U.S. 82% of the Internet users purchased at least one product or service online [ 7]. The most popular goods for Japanese online shoppers are computer-related products, purchased by 55.6% of those who shopped online at least once. Clothing was ranked the number one item that non-Internet users want to buy in future when they get Internet access [4]. Average user shopped online 3.76 times per year [ 8] and spent 35,000 yen per year [ 9].

As of April 2000, there are more than 25,000 Japanese online shops and more than 680 shopping malls [ 10]. In 1998 business-to-consumer trade accounted for .02% (8,685 billion yen) of the total household expenditure in Japan. However, it is expected to rise 71,160 billion yen in revenue by 2003 according to a survey by the International Trade and Industry Ministry and Andersen Consulting. Andersen estimated that business-to-consumer e-commerce in Japan was four to five years behind the U.S., but the gap would close to three years by 2003 [11].

As e-commerce is multi-dimensional, it may not be fair to estimate how many years Japan is lagging behind based on the U.S. e-commerce model. In one aspect, non-PC Internet connections, Japan is ahead of the U.S. In Japan many business men and women and students commute every day and spend a number of hours in public transportation. As a result, mobile communication devices such as PHS, cellular phones, and pagers are very popular and come in a wide variety. NTT Mobile Communications Network, Japan's leading mobile phone operator, and its competitors, Nippon IDO Tsushin and DDI Cellular Group, are already offering mobile data services ranging from home banking and news headlines to restaurant guides and weather reports. With their tiny cellular handsets, users can also send and receive e-mail and develop their own home pages.

Another very unique aspect of e-commerce in Japan is the role "conbinis" (convenience stores) play in promoting e-commerce among consumers in Japan. Conbinis in Japan are much more than convenience stores in the U.S. They are ubiquitous and have become a part of every day life in Japan. There are more than 50,000 conbinis in Japan and those conbini chains have sophisticated computer and distribution expertise [ 12]. In Japan where the use of credit cards is not as common as in the U.S. and people are still wary of using the credit cards for online shopping, conbinis could fill a gap between consumers and online retailers, and play a key role in e-commerce. The conbinis are vying to be the place the consumers can go to pay in cash for merchandise ordered online.

Conbinis can also play an important role in the distribution of goods ordered online for those people who are not home during the day as unlike in the U.S., Japanese parcel delivery services will not leave packages unattended in front of doors. Picking up ordered goods at a conbini is not only beneficial to consumers but also to online retailers as consolidating package deliveries at central locations significantly reduces cost [ 13]. Furthermore, for those people who don't have Internet access at home, the conbinis are installing online shopping terminals right in the store so that people can shop online at the terminals and pay immediately at the register.

Lawson, the second largest conbini chain after 7-Eleven, has installed online shopping terminals called Loppi in each of its 7,200 outlets [ 14]. Shoppers in a Lawson store sign on the Loppi terminal to scan product information, make reservations for a variety of products and services, and in the end receive a paper receipt. Those terminals are connected to the in-store POS register where shoppers take their receipts to pay for their purchases. Actual products will be delivered to the store a few days later for customers to pick up, or will be delivered to the customer's home [15].

Seven-Eleven Japan Co., the largest conbini chain, has been teaming up with Softbank, Tohan, and Yahoo Japan to sell books, CDs, and videos online since November 1999. It also announced in January 2000, that it would tie with NEC, Nomura Research, Sony Corp. and others to form a "Japanese-style e-commerce" venture, called 7dream.com [ 12]. Like Lawson's Loppi, 7-Eleven plans to install online multimedia terminals in all 8,000 7-Eleven stores in Japan by June 2001 in addition to launching a Web site that will offer travel-related services, music CDs, ticket sales, books, rental car reservation services, and other goods and services.

Though it is still a nascent state, it appears that an e-commerce model that is unique and different from that of the U.S. is emerging in Japan. When the Internet arrived in Japan, much of the early work on it just imitated what Americans were doing. Gradually Japanese have adopted the Internet into their existing culture and creating unique business models that simply work better.

Content Analysis of Popular Web sites in Japan and the U.S.

Examining the Internet and e-commerce in Japan as a case study of cultural differences from those in the U.S., the following sections will present the results of a content analysis of the top 50 most visited Web sites in each country examined in November 1999 and in May 2000. The purpose of this analysis is to examine differences in content strategies, design schemes, cultural concerns, and e-commerce strategies, and to suggest strategies for e-commerce/e-business targeting Japanese audiences.

Method

A content analysis was conducted on the top 50 Web sites in the U.S. and in Japan in November 1999 and in May 2000. The top 50 most visited U.S. web sites were selected based on Media Metrix's top domain ranking (see Appendix 1), and the top 50 most visited Web sites among Japanese were selected based on Nikkei BP Internet ranking (see Appendix 2). As for the Nikkei BP Internet ranking, there are two rankings listed: home access and business access. The home access ranking was used in this study assuming that home users are more likely to be the target audience of e-commerce sites than office users.

The total of 100 Web sites (i.e., 50 U.S. sites and 50 Japanese sites) for each period (i.e., November 1999 and May 2000) were coded according to the following categorization:

- Primary objective: portal, ISP, shopping, service, content provision, and corporate customer support.

A portal is a Web site that "is or proposes to be a major starting site for users when they get connected to the Web or that users tend to visit as an anchor site" [ 16]. Typical services offered by portal sites include a directory of Web sites, a facility to search for other sites, news, weather information, e-mail, stock quotes, phone and map information, and sometimes a community forum [ 16]. There are two different types of portals: general portals, serving general public, and specialized portals, serving a niche market.

An ISP site is a Web site of an Internet service provider dedicated to provide support information for their customers. Many portals have been started by ISPs, but the difference between a portal and an ISP site is that the information contained in an ISP site is basically limited to customer support information, such as access point information and system down announcements, while a portal offers a wider diversity of information and links.

A shopping site is a Web site where consumers can purchase goods online. Different payment systems were expected to be seen especially in Japanese e-commerce sites and the payment options were also coded among the shopping sites. Various payment options include credit card, personal check/money order, electronic money, cash transfer from either a bank or a post office (in Japan), payment through an ISP (meaning that the purchase charge are made to the ISP's billing system and the customer will receive one integrated bill for online purchases along with the monthly service charge from the ISP), COD, registered cash mail (available only in Japan), and payment at the nearest convenience store (available only in Japan).

A service site is a Web site that provides services (e.g., wallet services, e-mail services, sending cards, Web page building/hosting, points earning for free rewards, etc.) to consumers or business customers. These sites may offer services for free primarily to obtain user data or to expose users to advertisements, or for a fee.

A content site is a Web site that provides specific information (up-to-the-minutes news, weather information, entertainment) to users. This type of site can be subscriber-based or open to public and usually advertiser-supported.

A corporate site is a Web site of a brick-and-mortar company that sells goods and services to consumers. The primary function of this type of Web sites is customer support, public relations, and investor relations.

- Membership requirement: no membership, free membership, and fee-based membership

A Web site targeting general audience does not usually require any membership registration and allows anybody to access any section of the site. These sites are more likely to be supported by advertisers or by revenues from online transactions.

A Web site targeting members may allow anyone to access a certain section of the site (usually its opening page), but only those who signed up for membership, which will be either free of fee-based, will receive the full benefits of the site.

- Number of advertisements

The number of advertisements (including banner ads and icon ads, but excluding any promotional materials of the company itself) on the front page of a Web site is counted regardless of the size of the advertisements.Top 50 Web Sites in November 1999 and in May 2000

Among the 50 popular U.S. Web sites in November 1999, 23 (46%) of them did not make it in the top 50 list in May 2000. On the other hand, among the 50 popular Japanese Web sites in November 1999 only six (12%) did not make it in the list in May 2000. The top 10 sites in the November 1999 list remained as the top 10 sites in the May 2000 list as well, though the order below number three altered slightly. This reflects the competitive nature of the U.S. Internet industry and the stability of established Japanese Web sites.

Four sites in the Japanese top 10 list in both November 1999 and May 2000 (i.e., Yahoo!Japan, Microsoft, GeoCities, and MSN.com) originated in the U.S. These are simply U.S. sites or localized sites of sites originally developed in the U.S. This ranking shows the dominance of the U.S. even in foreign Internet markets.

Popular Web Site Categories

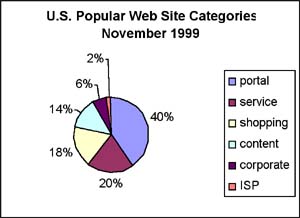

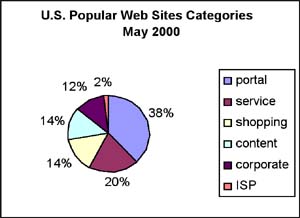

Among the 50 popular U.S. Web sites coded in November 1999, 20 of them are portals (40%), 10 are service sites (20%), nine are shopping sites (18%), seven are content sites (14%), three are corporate sites (6%), and one is an ISP site (2%). No significant change was observed in May 2000 in terms of the popular Web site categories in the U.S. Among the 50 popular U.S. Web sites in May 2000, 19 of them are portals (38%), 10 are service sites (20%), seven are shopping sites (14%), seven are content sites (14%), six are corporate sites (12%) and one is an ISP site (2%); see Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. U.S. Popular Web Site Categories

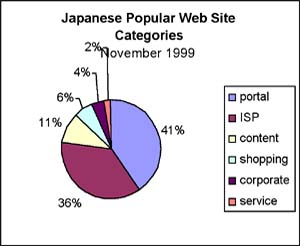

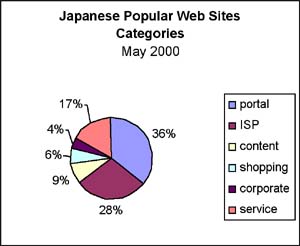

Among the 47 popular sites among Japanese Internet users (as three sites listed in the NikkeiBP November 1999 and May 2000 top Web sites, www.nifty.ne.jp, www.infoweb.ne.jp, and www.nifty.com are merged into www.nifty.com, two sites were extracted from the list; and one site, www.dti.ne.jp, could not be reached), 19 of them are portals (40.4%), 17 are ISP sites (36.2%), five are content sites (10.6%), three are shopping sites (6.4%), two are corporate sites (4.3%), and one is a service site (2.1%). Out of the 47 sites, five sites are in the U.S. top 50 sites (Microsoft.com, msn.com, netscape.com, geocities.com, and real.com). The notable is the increase in the number of services sites as a half of the new Web site entry in May 2000 is service sites (freeweb.ne.jp, sakura.ne.jp, and tripod.co.jp).

Figure 2. Japanese Popular Web Site Categories

In both the U.S. and Japan, portals are the most popular type of sites (no surprise since by definition portals should be the sites which attract a great deal of traffic). Approximately 40% of the top Web sites are portals. Most portal sites on the Japanese list are general portals targeting the general public while many U.S. portal sites are specialized portals such as women.com, eUniverse network, and IWON.com, targeting specific audiences.

There is a notable difference in the second popular Web site category between the U.S. and Japan. In the U.S. ranked second are service sites that offer free or fee-based services to their users. Examples of service sites in the U.S. are Passport.com, that offers free services that make online shopping faster and easier; Hotmail.com, that offers free e-mail accounts to its members; and Bluemountainarts.com, that offers free electronic greeting card sending services. Though service sites are popular, it seemed difficult to sustain this popularity. Six out of the ten service sites that appeared in the top 50 list in November 1999 did not return in May 2000. Instead, eight new service sites appeared in May 2000, including personal publishing, lottery services, and reminder services.

On the other hand, in Japan service sites were not yet popular (only one out of 47 is categorized as a service site) in November 1999. Their number increased to eight in May 2000 and ranked third following portal sites and ISP sites. As mentioned earlier, three new Web site entries in the May 2000 list are service sites (freeweb.ne.jp, sakura.ne.jp, and tripod.co.jp).

When the content analysis was conducted in November 1999, 17 out of 47 sites in the Japanese top 50 list were ISP sites while only one ISP site was found in the U.S. list. At the same time, service sites are the second popular category in the U.S. list while there was only one service site in the Japanese list. The difference can be attributed to the fact that Internet users in Japan are novices compared to U.S. users; they had not realized the full potential of what the Internet could offer. Since Japanese users at this point were basically concerned with getting connected to the Internet, it's not surprising that there was a lot of traffic to ISPs. It also might be simply that Japanese Internet users used their ISPs home pages as their default page for their browsers.

Six months later, the number of service sites in the Japanese top 50 list increased while the number of ISP sites decreased. This change might be a sign of increasing maturity of Japanese Internet users seeking some specialized services on the Web.

Most Japanese portals evolved from former "pasokon tsushin" [personal computer communications] service providers, equivalent to pre-Internet era online services in the U.S. such as Prodigy and CompuServe. The two most popular sites in Japan following Yahoo Japan and Microsoft Corp. are @nifty and Biglobe, both of which are former "pasokon tsushin" service providers offered by Fujitsu and NEC respectively. The combined number of members reaches approximately 5.5 million in June 1999 [ 17] that accounts for more than 40% of all Internet users in Japan. Other popular sites are ISP sites such as Fujitsu's InfoWeb (which was merged with Nifty-serve and became @nifty) and Sony's So-net. In 1999, InfoWeb has 673,000 members and So-net has 650,000 members [ 17]. Those numbers are rather small compared with those of Nifty Serve and Biglobe that have over 2.7 million members each.

Among the four Japanese content provision sites analyzed May 2000, two (asahi.com and nikkei.co.jp) were newspaper sites; no U.S. newspaper sites made the top 50 list. The notable content provision sites in the U.S. list are onHealth that offers a database of more than 3,000 drugs and vitamins, and the Weather Channel that provides nationwide up-to-date weather information.

As for shopping sites, there are two kinds: shopping mall sites where they provide infrastructure services to small and medium-size retailers who want to set up shops online, such as Rakuten; and those shopping sites that sell goods and services directly, such as Amazon.com and CDNow. In the U.S. those specialized large scale shopping sites established their brands early and earned more than 100 million U.S. dollars in 1999 [ 18]. On the other hand, in Japan about 53% of the online shops are small scale shops with revenues less than 200,000 yen (approximately 1,900 U.S. dollars) per month and the shopping mall idea seems to be popular among both consumers and shop owners.

Membership Requirements

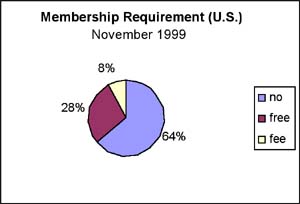

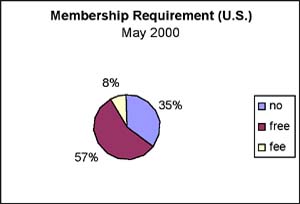

Web sites were also coded in terms of whether they require membership registration to receive certain benefits. In November 1999, the majority of the U.S. Web sites (64%) on the list did not require any membership; 28% of them require free membership registration; and 8% require a fee-based membership. In May 2000, the number of U.S. Web sites that offer free services such as e-mail services, personalization, Internet access, and Web space upon membership registration increased to 29 (58%) while the number of Web sites that do not require any membership registration decreased to 18 (36%). Free e-mail services are especially popular and many more people are willing to register for these services. Since the effectiveness of general advertisement on the Web has been questioned, more sites are turning to registration to build a customer database for personalized marketing and for ad exposure in exchange for personalized services.

Figure 3. U.S. Membership Requirement

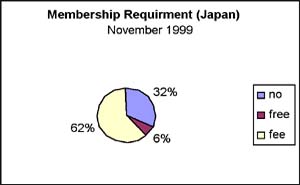

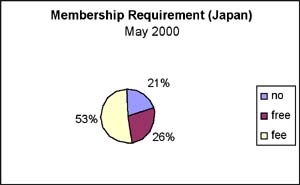

The majority of Japanese sites on the November 1999 list (62%) and on the May 2000 list (53%) require a fee-based membership, though the number decreased in 2000. Thirty-two percent in November 1999 and 21% in May 2000 required no membership registration. Following the U.S. model, the number of sites that require free membership registration increased from 6% to 26%.

Figure 4. Japan Membership Requirement

From the e-commerce point of view, the differences in membership requirements between the U.S. and Japan reflects two different Web cultures. In the U.S. purchasing goods and services online using a credit card is most prevalent; anyone can visit an e-commerce site and purchase goods or services online using a credit card. In Japan credit cards were not used commonly yet in November 1999 and people seemed to be wary of using a credit card online; most e-commerce sites in Japan used direct deposit payment from the bank specified by a customer. In order for the direct deposit payment system to work, the site has to know each customer's bank account. For this reason, an e-commerce site was usually for the members of particular online service providers such as Niftyserve and Biglobe; only members could purchase goods and services offered by the site. Then, the online retailers or service providers could charge the prices and fees to the member's bank account directly.

This difference between U.S. and Japanese sites is changing. The number of fee-based membership sites on the Japanese list decreased between 1999 and 2000 while the number of free membership sites increased, becoming more similar t U.S. Web sites.

Payment Systems

For online shopping sites in the U.S. and in Japan, payment options were analyzed. Most U.S. shopping sites offer only credit card payment either online or off-line (meaning a customer has to call a given telephone number to provide a credit card number or fax credit card information to a given fax number). According to the report by NetSmartAmerica.com [ 7], 70% of those who have shopped online at least once paid with a credit card. On the other hand, the most common method of payment among Japanese online shopping sites in November 1999 and in May 2000 was C.O.D.; cash payment upon the delivery and receipt of ordered goods, reflecting the Japanese culture of cash-based payment. The pick-up/payment can be done at the nearest combini store so that the buyer doesn't have to be at home to receive the shipment.

Offering the option of credit card payment was rare for Japanese sites as it was difficult to make a contract with a credit card company in Japan (also the commission was higher for online retailers). As a result there have been a variety of payment methods offered by Japanese online shopping sites, including prepaid electronic money, virtual credit card systems, and payment through monthly telephone bills. However, the situation has changed and most of those Japanese e-commerce sites analyzed in May 2000 offer credit card payments as the primary payment method, reflecting more acceptance of electronic commerce in Japan.

Rakuten, the largest online shopping mall in Japan started in April 1997, offers a variety of payment methods including credit card, postal wire, C.O.D., payment at a 7-Eleven shop, and iREGi which is the payment through the ISP monthly billing described later. Another popular Japanese shopping site, Vector, sells all their goods (i.e., computer software) online. The payment options they offer include credit card payment (as the default); payment at the nearest store of 11 conbini chains, including 7-Eleven, Lawson, Family Mart, Circle K, Thanks, Mini Stop, am/pm, Three F, Popura, CoCo Store, and SaveOn (not all the goods offer this option of payment); debit card payment; and, SET (secure electric transaction). In order to use SET as the payment method on the Japanese site, a shopper has to apply for a credit card first to either DC or SAISON (these are the only companies which currently deal with SET). Once approved, the person will receive software called "wallet". After a user installs this "wallet" software, transactions can be made online.

Some major online service providers in Japan such as @nifty, BIGLOBE, and So-net adopted the system with which members can shop online conveniently without providing credit card numbers or setting up a direct deposit to the bank specified by the retailer. Members who choose the member's-only payment option will pay for goods or services ordered online through the regular monthly bill of the service provider. This is a convenient payment method for both service providers or venders and consumers as minute fees can be charged with ease.

Advertisements

As Internet advertisement revenues in 1999 grew to $4 billion in the U.S. [ 19] and to $223 million in Japan [ 20], it was expected that all the popular sites would be flooded with ads. However, overall the numbers of ads were smaller than originally expected. In U.S. popular Web sites, the average number of ads appearing on the opening page was 1.3 in November 1999 and 1.1 in May 2000, while in Japanese sites the number was slightly higher or 1.6 in November 1999 and 1.2 in May 2000. This might be due to the fact that the only the ads which appear on the front page of each site were counted though many ads were placed on subsequent pages.

Among the 50 U.S. popular sites analyzed in November 1999, only two sites (Warner Brothers and Buy.com) carried more than five ads, and only three sites (Shopnow Network, Women.com, and MapQuest.com) in May 2000. Among the 47 Japanese popular sites, six sites in November 1999 and three in May 2000 carried more than five ads. In both U.S. and Japanese sites, overall a banner ad is used sparingly, and if a site carried more than two ads, the size of the ads tended to be smaller (1.5" x 0.5"). In addition, it is notable that in both the U.S. and Japan many online companies fill advertising space on their sites with their own banner ads. This may be an indication of the difficulties in sustaining advertisement-supported operations on the Web.

Conclusions

The Internet, which was originally started in the U.S. as a tool for researchers to share their data and resources and to collaborate on projects, now has matured to be a global infrastructure of communication and businesses. Japan, which a few years ago lagged far behind the U.S. in terms of adoption of Internet technology, is rapidly catching up with the U.S. in terms of Internet user profiles and the prevalence of e-commerce. Furthermore, e-commerce models that are unique to Japan are emerging though the success of such models is yet to be seen. This paper examined Japanese e-commerce in comparison with that of the U.S. Though the Internet has been dominated by Americans, its growth has been most pronounced outside of the U.S. It will be interesting to see how companies in other countries are, or will be, adopting their own unique models of e-commerce. Now that Internet has become more than a tool of global communication and become the place to conduct global businesses, no global company can ignore the culture and customs of different countries where it is expanding. The localization of an e-commerce site involves not only language translation but also adoption of local cultures and social systems. A company who is aware of such differences and serves customers with different needs will thrive in the 21st century.

About the Author

Kumiko Aoki is Associate Director of the Communication Research Center and Assistant Professor of Communication at the Boston University. She received her Ph.D. in Communications and Information Sciences from the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Her research interest revolves around the Internet, ranging from cultural differences of its use, educational methodological applications of the Internet, interactivity on the Web, and methodological issues of using the Internet as a data collection tool.

E-mail: kaoki@bu.eduNotes

1. Global Reach, 2000. "Global Internet statistics (by Language)," at http://www.glreach.com/globstats

2. CTO FirstMover, 2000. "As the net goes global, U.S. e-commerce dominance slips," (18 September), S16-S17.

3. Business Wire, 1998. "Web sites for an international audience explored by technical communicators at Anaheim conference."

4. Ministry of Post and Telecommunications, 2000. Tsushin Hakusho [Telecommunications white paper]. Tokyo: Okurasho Insatsukyoku.

5. J. Epstein, 1998. "Hurry up & wait: Electronic commerce in Japan," Computing Japan (July), at http://www.cjmag.co.jp/magazine/issues/1998/july98/epstein.html

6. AsiaBizTech, 1999. "Two thirds of Japanese users buy online," (27 September), at http://www.nua.ie/surveys/index.cgi?f=VS&art_id=905355302&rel=true

7. NetSmartAmerica.com, 2000. "America.com: What makes America click," at http://netsmartamerica.com

8. AsiaBizTech, 1999. "Over 18 Million Online in Japan in April 1999," (10 September), at http://www.nua.ie/surveys/index.cgi?f=VS&art_id=905355268&rel=true

9. DSA Group, 1999. "The Internet user and online commerce in Japan: Executive summary," at http://www.dsasiagroup.com/Executive%20Summary.htm

10. Nomura Sogo Kenkyujo, 1999. "Cyber-business statistics in Japan," at http://www.ccci.or.jp/cbcb/cb_stat.html

11. Daily Yomiuri, 1999. "Japanese ecommerce to top 1 trillion yen," (8 April), at http://www.nua.ie/surveys/index.cgi?f=VS&art_id=905354826&rel=true

12. P. Landers, 2000. "Seven-Eleven Japan, Sony set e-commerce plan," Wall Street Journal (7 January).

13. T. Clark, 1999. "What's the difference between e-tailing and mail order?" Japan Internet Report (July/August), number 40, at http://www.jir.net/jir7_99.html

14. P. Landers, 1999. "In Japan, the hub of E-commerce is a 7-Eleven," Wall Street Journal (1 November).

15. K. Osborn, 1998. "We have seen the future, and it is conbini," Computing Japan (October), at http://www.cjmag.co.jp/magazine/issues/1998/oct98/osborn.html

16. C. Nowlin, 1999. "What is ... a portal and portal space (a definition)," at http://www.whatis.com/portal.htm

17. New Media Development Association in Japan, 1999. "Denshi nettowaaku jittaichousa kekka" [The result of the survey of the status of electronic networks in Japan] (28 October).

18. Society for the Study of Internet Business, 1999. Internet Business White Book 2000. Tokyo: Softbank Publishing.

19. Jupiter Communications, 2000. "Press releases," at http://www.jup.com

20. Dentsu. 2000. "News release," (15 February), at http://www.dentsu.co.jp/DOG/news

Appendix 1: Media Metrix Top 50 U.S. Domain Ranking in November 1999 and in May 2000

November 1999 May 2000 1 Yahoo.com 1 AOL Network* - Proprietary & WWW 2 Aol.com 2 Microsoft Sites* 3 Msn.com 3 Yahoo Sites* 4 Microsoft.com 4 Lycos* 5 Geocities.com 5 Excite@Home* 6 Netscape.com 6 Go Network* 7 Go.com 7 About.com Sites* 8 Amazon.com 8 NBC Internet* 9 Passport.com 9 Amazon* 10 Hotmail.com 10 Time Warner Online* 11 Lycos.com 11 AltaVista Network* 12 Excite 12 Ask Jeeves* 13 Bluemountainarts.com 13 Real.com Network* 14 Tripod.com 14 Go2Net Network* 15 Angelfire.com 15 eBay* 16 Ebay.com 16 LookSmart* 17 Real.com 17 eUniverse Network* 18 Altavista Search Services 18 CNET Networks* 19 Hotbot.com 19 ZDNet Sites* 20 Snap.com Search & Services 20 Infospace Impressions* 21 About.com 21 JUNO / JUNO.COM 22 Cnet.com 22 IWON.COM 23 Xoom.com 23 EarthLink* 24 Looksmart.com 24 Viacom Online* 25 ZDNet 25 FortuneCity Network* 26 Goto.com 26 Weather Channel, The* 27 Msnbc.com 27 CitySearch-TicketMaster Online* 28 Smartbotpro.net 28 GoTo* 7,576 29 Infospace.com 29 AT&T Web Sites* 7,365 30 Barnesandnoble.com 30 American Greetings* 7,345 31 Icq.com 31 Snowball* 7,062 32 M0.net 32 Travelocity* 6,926 33 Macromedia.com 33 iVillage.com:The Womens Network* 6,683 34 Askjeeves.com 34 Shopnow Network* 6,610 35 Sony Online 35 FREELOTTO.COM 6,435 36 Earthlink.net 36 Women.com Networks, The* 6,252 37 Warner Bros. Online 37 SONY ONLINE* 6,143 38 Etoys.com 38 SMARTBOTPRO.NET 6,124 39 Mypoints.com 39 News Corp. Online* 5,823 40 Toysrus.com 40 LIFEMINDERS.COM 5,753 41 Buy.com 41 MAPQUEST.COM 5,746 42 Weather.com 42 Uproar Network, The* 5,741 43 Pathfinder.com 43 McAfee.com Sites* 5,673 44 Cdnow.com 44 MYPOINTS.COM 5,528 45 Digitalcity.com 45 Homestead Sites* 5,424 46 Simplenet.com 46 PASSTHISON.COM 5,194 47 Directhit.com 47 OnHealth* 5,176 48 Expedia 48 BARNESANDNOBLE.COM 5,167 49 Cnn.com 49 Theglobe.com Network* 5,141 50 Windowsmedia 50 BONZI.COM 5,115

Appendix 2: Nikkei BP Top 50 Domain Ranking for Japanese Home Internet Users in November 1999 and in May 2000

Domain Reach (%) Sessions per User Page Views per User Domain Reach (%) Sessions per User Page Views per User yahoo.co.jp 62.2 yahoo.co.jp microsoft.com 51.0 microsoft.com nifty.ne.jp 48.5 biglobe.ne.jp biglobe.ne.jp 46.1 geocities.co.jp msn.com 38.4 nifty.com geocities.co.jp 35.9 nifty.ne.jp dti.ne.jp 35.7 dti.ne.jp infoweb.ne.jp 35.6 so-net.ne.jp so-net.ne.jp 32.9 msn.com 10 hi-ho.ne.jp 29.1 hi-ho.ne.jp 11 nifty.com 27.5 infoweb.ne.jp 12 mbn.or.jp 26.6 mbn.or.jp 13 bekkoame.ne.jp 24.7 lycos.co.jp 14 rim.or.jp 24.2 goo.ne.jp 15 asahi-net.or.jp 23.3 odn.ne.jp 16 goo.ne.jp 23.1 asahi-net.or.jp 17 justnet.ne.jp 22.1 justnet.ne.jp 18 3web.ne.jp 21.2 rim.or.jp 19 interq.or.jp 19.4 interq.or.jp 20 vector.co.jp 19.3 20 iij4u.or.jp 21 odn.ne.jp 18.2 neweb.ne.jp 22 infoseek.co.jp 17.9 infoseek.co.jp 23 big.or.jp 17.7 bekkoame.ne.jp 24 cplaza.ne.jp 17.7 ocn.ne.jp 25 iij4u.or.jp 17.2 rakuten.co.jp 26 lycos.co.jp 16.8 dion.ne.jp 27 impress.co.jp 14.9 plala.or.jp 28 nikkeibp.co.jp 14.7 freeweb.ne.jp 29 excite.co.jp 14.5 impress.co.jp 30 din.or.jp 14.2 nikkeibp.co.jp 31 isize.com 14.2 sakura.ne.jp 32 tcup.com 14.0 highway.ne.jp 33 plala.or.jp 14.0 tcup.com 34 netscape.com 13.8 msn.co.jp 35 highway.ne.jp 13.3 vector.co.jp 36 rakuten.co.jp 13.3 tripod.co.jp 37 ocn.ne.jp 13.3 3web.ne.jp 38 iijnet.or.jp 13.3 big.or.jp 39 sony.co.jp 13.1 cplaza.ne.jp 40 sphere.ne.jp 13.0 iijnet.or.jp 41 cool.ne.jp 13.0 isize.com 42 geocities.com 13.0 excite.co.jp 43 real.com 12.1 cool.ne.jp 44 asahi.com 11.7 real.com 45 dion.ne.jp 11.7 din.or.jp 46 neweb.ne.jp 11.4 geocities.com 47 nikkei.co.jp 11.2 www.ne.jp 48 airnet.ne.jp 11.0 xaxon.ne.jp 49 nikkansports.com 10.9 nikkei.co.jp 50 sannet.ne.jp 10.9 asahi.com

Editorial history

Paper received 28 September 2000; accepted 1 November 2000.

An earlier version of this paper was presented at INET 2000, the 10th Annual Internet Society Conference, in Yokohama, Japan on 21 July 2000.

Copyright ©2000, First Monday

Cultural Differences in E-Commerce: A Comparison Between the U.S. and Japan by Kumiko Aoki

First Monday, volume 5, number 11 (November 2000),

URL: http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue5_11/aoki/index.html