Read related articles on Internet publishing

Read related articles on Internet publishing

Book jackets provide a model for access to documents on the World Wide Web. They demonstrate a means for making available many of the representational attributes important to making relevance judgments. Such attributes have been posited for retrieval models for some time, but have not been implemented in most formal access systems. Even in the Web environment physical availability is not the same as accessibility. The attribute categories discussed here emerged from 228 book jackets for non-fiction works in a medium size academic library. Models of document searching and book jacket design are discussed in relation to the individual scholarly searcher and new modes of document searching.

Contents

Assertion

Background

Initial Examination of Book Jackets

Emergent Categories

Content Analysis of Sample from an Academic Library

Discussion

Notes

ReferencesAssertion

The World Wide Web provides unrivaled physical availability of documents, yet, physical availability of documents is not the same as accessibility. In the words of Wilson, even documents in hand may be inaccessible linguistically, conceptually, or critically [1]. A rather more antique technology provides a model for improving accessibility. The book jacket on an academic book provides a user-centered access mechanism. Unlike the representations in standard access systems, the book jacket is a multi-faceted and partly evaluative representation of the book. As such, it can provide a significant means for the scholarly searcher to reduce search time and to make informed selections, providing topical information and significant clues as to linguistic, conceptual, and critical suitability. Of course, the book jacket serves two utilitarian purposes that are not directly user-centered. It provides some degree of protection for the document and it serves as a sales tool - even academic presses have to be concerned with sales figures. However, a good deal of expense and effort go into the construction of the academic book jacket to benefit the work's subject and audience [2].

Background

Frequent casual observations of book jackets being removed from their books by various technical processing units in academic libraries stimulated this exploration. The book jackets may be disposed of or they may be put into give-away boxes. They are seldom seen incorporated into any form of access mechanism.

Figure 1. Free Book Covers - Help Yourself

"No, you can't always judge a book by its cover, but ... it's damn near impossible to sort through and evaluate thousands of books without them. ... I would observe that the help-to-hype ratio for most book jackets is pretty high ..." [3].A serendipitous discussion with the sales manager for an academic press provided insights into the book jacket design process. The frequent occurrence of the term "representation" during a "walk through" of a jacket design provided impetus to consider the possible role of book jackets in access systems.

Examination of new commercial models for access to books (e.g., amazon.com; Libraries Unlimited; MIT Press) shows a trend toward providing more descriptive and more evaluative information to a user than is customary in card catalogs or traditional online access systems. They provide a rich palette of entry points and selection criteria. At the same time, however, many still display a paucity of both descriptive and evaluative attributes when compared with the book jacket.

Many searches in document collections are conducted with no clearly defined target. That is, the exact title or author or call number is not known. Even when the searcher has a reasonably well-articulated information requirement, just which documents will satisfy that requirement are not self-evident. Reducing the number of documents to be examined and reducing the time to examine each document are fundamental reasons for the construction of access mechanisms - some manner of representation of the documents.

Representation here will taken to be a system for highlighting salient characteristics of a document and, necessarily, leaving some characteristics behind [4]. Some aspects of the document will be used to stand in place of the whole for some purpose. The purpose assumed at the time of representation will determine just which characteristics will serve as surrogates for the whole. The representation available at the time of the search will determine what can be accomplished with the representation. It is important to note information is lost in the representation. The surrogate has only some of the characteristics of the original; it performs only some of the functions of the original; both its utility and its faults lie in its smaller size.

Probability of satisfaction has been proposed as the operative concept for information retrieval [5]. Assuming that the indexing process had adequately and accurately identified all the salient characteristics, the system could predict the likelihood that a particular requirement could be satisfied by any particular document.

Typical retrieval systems have been constrained from presenting as many salient characteristics as necessary. That is, they represent primary topics within a work and they have generally set an arbitrary, operational number of representation elements (for example, the three Library of Congress subject headings typically applied to books). Typical retrieval systems have also neglected to include a set of factors which also determine whether a document will be satisfactory (or satisfactory to some significant degree). These factors include, among others:

This set of factors echoes Wilson's assertion that the physical availability of every document in the world does not necessarily equate with accessibility. Recall that a work may be linguistically inaccessible, conceptually inaccessible, or critically inaccessible (Wilson, 1977). We might, then, suggest a scholar searching through any significant number of works would benefit from representations of these factors. There are generally a large number of informational elements on an academic book jacket; could we say that these provide useful representation of both the aboutness of a document and the additional factors influencing likelihood of satisfaction?

- comprehensibility,

- credibility,

- importance,

- timeliness, and

- style.

Initial Examination of Book Jackets

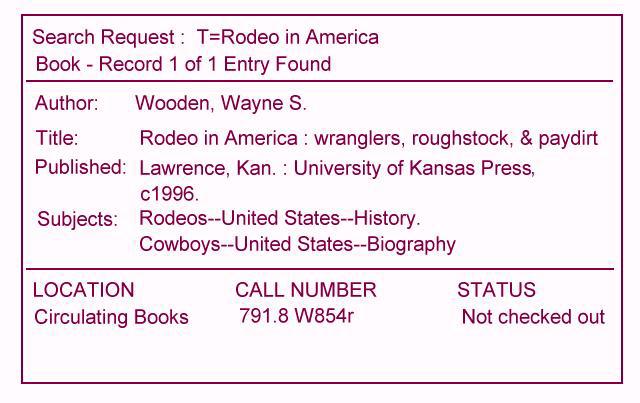

The initial examination of book jackets began with a few titles from the University Press of Kansas, of which Rodeo: Wranglers, Roughstock, and Paydirt (Wooden & Gaven, 1996), presented in Figure 2 (monochrome version of front cover) and Figure 3 (interior blurb), is one example.

Figure 3 presents a piece of descriptive material. This is, in effect, an extended subject descriptor. The reader is told that the work is about:

- rodeo as a national pastime,

- essential character of rodeo,

- current rodeo culture, and

- rodeo's hold on American imagination.

The reader is also given the first hint of the authorial approach of the work with the phrases "celebrates" and "behind the chutes."

A second portion of the book jacket is shown in Figure 4; with this, the readeris presented with a second set of style attributes: "anecdotes and observations." In addition, the reader learns that work is also "clarifying its many dimensions... ." A second and deeper (in the sense of relating to portions of the work rather than the work as a whole) list of subjects is presented here.

Emergent Categories

The categories derived from the book jackets fell into the following categories:

- credentials of authors;

- credentials of reviewers;

- evaluative comments;

- for whom book intended;

- graphics;

subjects (at different depths);

- style; and,

- summary.

These basic categories emerged from examination of a dozen book jackets. Not all are evident in each and every source. As is typical with content analysis categories, precise boundaries and membership characteristics were difficult to establish. Examples from Rodeo in America (see Table 1) indicate the type of material associated with each of the categories.

Table 1: Examples of Attributes in Each Category Credentials of authors Wooden is professor of Sociology and coordinator of the Criminal Justice and Corrections Program at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. He is author of ... Ehringer is a freelance journalist and former media assistant at the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association. He has published more than 500 articles in journals such as ... Credentials of reviewers White, publisher of Western Horseman Slatta, author of Cowboys of the Americas Hoy, author of Cowboys and Kansas Evaluative comments The definitive book on rodeo...most comprehensive, probing look to date... A book like this...provides...a sense of what rodeo is really like. ...entertaining and highly readable Intended audience ...guide for afficianados and novices alike ...provides the uninitiated with... Subjects Character of rodeo culture today ...why it retains such a strong hold on the American imagination Glamour and glory, hazards and hardships, ...many dimensions as a sport, business, community event, family tradition, and pop culture icon Bareback and bull riders, calf ropers and steer wrestlers...clowns, [etc.] Allure and demands of rodeo life Style Taking the reader behind the chutes Filled with telling anecdotes and insightful observations Based on research and interviews conducted at the National Finals... ...highlights rodeo's..., while clarifing its... Graphics Repeated image of a bronc rider (see Figure 2) with mixed Western fonts. Shotts (1997) detailed the process of selecing the particular image for the cover, the color scheme, and the fonts. A full color mock up was presented to colleagues at other presses. The critique resulted in reversing the photograph in order to work with the cover text (even though this reverses the handedness of the rider). Summary three paragraphs ofsummary material

Content Analysis of Sample from an Academic Library

An instrument for analyzing a larger sample of book jackets was constructed from the categories that emerged in the initial consideration. For this study, the actual contents were not gathered, only the presence or absence of material appropriate to each category was noted. Graphics were not noted because every book jacket, by definition, had some form of graphical design even if only color selection and font.

Each week for eight weeks, a random sample of 50 book jackets was selected from the box of jackets discarded at the circulation desk (generally when a new book was checked out for the first time). " Jackets from novels and duplicates were eliminated from the sample group, as were those that had been damaged. The final set for examination consisted of 228 items. Table 2 presents the results of the analysis.

Table 2: Results of Content Analysis of Book Jackets Book Jacket Attribute Number of Covers with Attribute Percentage of Total subject indicators 219 96.1 evaluative statements 183 80.3 summary 227 99.6 author credentials 223 97.8 user description 107 46.9 reviews (535; 3.4/title) 157 68.9 reviewer credentials 144 91.7 (titles with reviews) 63.2 (all titles)

Discussion

Representation implies loss of some information. Loss of information is the strength of the surrogate as a search tool. Less information with which to engage means less time in search space. Of course, this depends on the surrogate containing information appropriate to the search. When documents are represented only by broad topical concepts presented in system terms, the likelihood of an individual searcher missing useful material is high.

Even in the case of Rodeo in America, in which a significant keyword appears in the title, the record found in the system, as represented in Figure 5, shows very little information on which to make an evaluative selection.

Note that for a Subject Search, one must input exactly the subject residing in the system. Thus, American Rodeos and Rodeo Cowboys would not work. Similarly, Cowboys would not work for a Keyword Search. While it is the case that Web search engines typically use more sophisticated counts of words as well as thesauri, the initial presentations of results are still essentially lists of unevaluated documents.

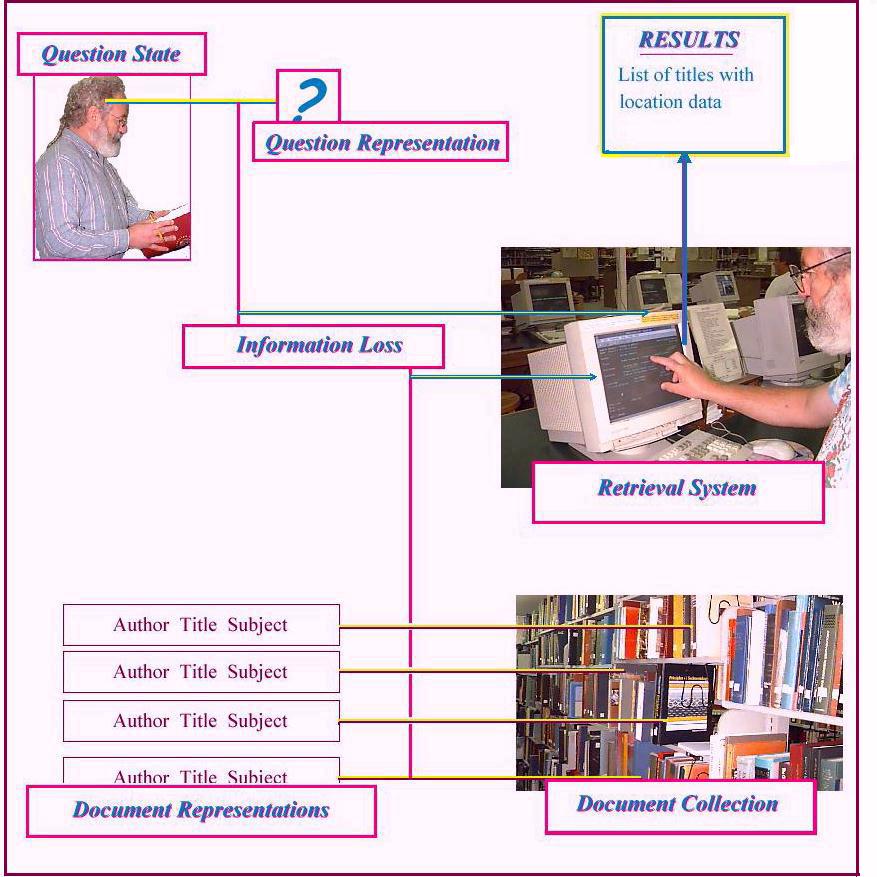

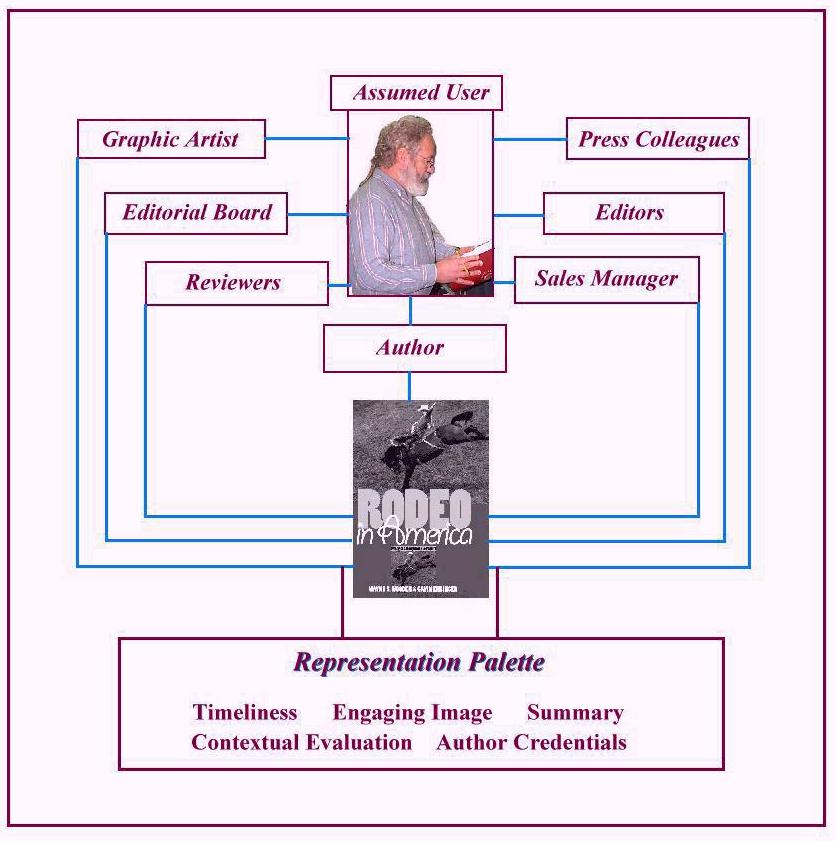

In a document search there are at least two significant points where information is lost: the surrogates for the documents are shorter than the originals; and the questions put to the system may be much smaller than the mental gap driving the search. A searcher cannot simply walk up to a reference desk or log on to a search engine and have the system "know" what the mental gap is. The searcher must give some voice to the requirement. Figure 6 represents the relationship between a searcher and a document collection.

Book jackets present several types of salient characteristics of the documents they represent. We might say that they present "conversational representations" because those engaged in representing the document have a vested interest in presenting characteristics of value to searchers and in presenting those characteristics in a manner useful to the searchers. The categories which emerge from examining book jackets demonstrate a concern with the functionality of the representation; they present responses to the anticipated questions: "what can I do with this book?"; "Do I have reason to trust in its cognitive authority?" Reviewers represent a portion of the likely readership.

Figure 7 presents the construction of the "representation palette". Each of several people engaged in the representation process holds in mind an image of the prospective user(s) profile(s). Subject indicators and summaries appear on the vast majority of the book jackets examined. These provide the form of topical representation customary in access systems, with two significant differences. On the whole, they leave less behind in the representation tradeoff and they are in the vocabulary of the assumed user group.

Topical representations and descriptive representations such title, publisher, and number of pages remain stable over time; they may be termed diachronic. Evaluative statements, author credentials, user description, reviews, and reviewer credentials all speak to a different sort of representation. These are of the sort suggested by Maron and Wilson and may be termed synchronic. Timeliness, readability, and credibility are among the synchronic characteristics often presented on book jackets.

Author credentials and reviews speak to the cognitive authority of the work in hand. Of course, reviews are highly likely to be positive; however, Shotts notes that most academic publishers look for reviews which will also represent the content and style of the work and speak to the targeted audience. If a reader is familiar with the reviewer's work or understands the value of reviewer credentials, these can be used to assess credibility. That is, a reader might say either "I don't know the author, but I like the reviewer's previous work so well I'll give this a try" or "I so dislike this reviewer's own work I can't imagine that I would find value in the book in hand." Book jackets, thus, provide both an enriched form of the representation seen in traditional access systems and a form of representation not often found in access systems yet important to evaluation and selection. The simple and immediate consequence of such an assertion is to ask why book jackets are so often discarded. Of course, the immediate response can be the expenditure of resources required to make such relatively fragile materials available in the environment of a large paper document collection.

Within the developing digital document environment, the logistics of providing both topical and functional or evaluative representation may prove less troublesome. Some organizations already provide enriched representations of the documents in their collections. The legacy of the book jacket as an enhanced representation palette can provide a substantial foundation for robust digital representations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to especially thank Denise Cottenmyer, doctoral student in the School of Library and Information Management, Emporia State University, for her early work on the book jacket project. A special debt of gratitude is owed to the staff of the University Press of Kansas who took time to walk us through the book jacket production process, in particular Fred Woodward and Susan Schott.

About the Authors

Brian C. O'Connor (Ph.D., Berkeley 1984) is now with the School of Library and Information Sciences at the University of North Texas. His areas of interest include access to image documents, retrieval system design, and scholarly browsing.

E-mail: boconnor@lis.admin.unt.eduMary K. O'Connor (MLIS, Berkeley, 1983) teaches in the areas of theory of organization of information and image access systems.

E-mail: 4oconor1@gte.net

Notes

1. Patrick Wilson, 1977. Public Knowledge, Private Ignorance: Toward a Library and Information Policy. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, p. 88.

2. AAUP Book, Jacket, and Journal Show, 1996. Show Catalog by the Book, Jacket, and Journal Show Committee of the American Association of University Presses, p. 1.

3. J. Dwyer, 1993. "You Can't Judge a Book without a Cover," Technicalities, volume 13, number 12, pp. 3-4.

4. David Marr, 1982. Vision: A Computational Investigation into Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, p. 20.

5. M. E. Maron, 1977. "On Indexing, Retrieval and the Meaning of About." Journal of The American Society for Information Science (January), pp. 38-43.

References

AAUP Book, Jacket, and Journal Show, 1996. Show Catalog by the Book, Jacket, and Journal Show Committee of the American Association of University Presses.

Dwyer, 1993. "You Can't Judge a Book without a Cover," Technicalities, volume 13, number 12, pp. 3-4.

M. E. Maron, 1977. "On Indexing, Retrieval and the Meaning of About." Journal of The American Society for Information Science (January), pp. 38-43.

David Marr, 1982. Vision: A Computational Investigation into Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

Susan Schott, 1997. Personal conversation with Sales and Marketing Director for the University Press of Kansas.

Patrick Wilson, 1977. Public Knowledge, Private Ignorance: Toward a Library and Information Policy. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

Copyright © 1998, ƒ ¡ ® s † - m ¤ ñ d @ ¥